To find out more about what we’re up to, watch this video.

Category: Adventures in archives

The Several Seals of Bella Hella

Today is International Women’s Day, and Imprint thought this would be a good time to tell you the story of a shrewd medieval businesswoman, from her first steps as an adult in her teens to holding an established position in her community.

In 1965 Francis Hill, writing on Medieval Lincoln, used some of the Dean and Chapter deeds to describe what was happening in the thirteenth-century Lincoln suburb of Butwerk. He described land in St Rumbold’s parish there ‘which once belonged to Matilda Drincalhut whose name suggests a street cry and its appropriate trade. Here too were Henry the illuminator, and Ralf the tailor’ (p. 161). All of this is true, but Hill ignores the person who is central to all these grants. When Imprint came to look at the deeds and the attached seals we found that the documents Hill used were all granted by one woman – Bella daughter of Alan Helle (once called Bella daughter of Alan of Glentworth) and that the sealing as well as the documents told us much more about Bella.

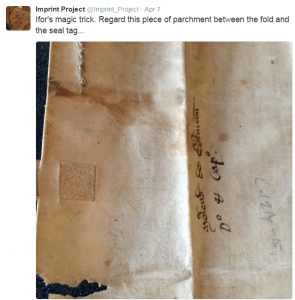

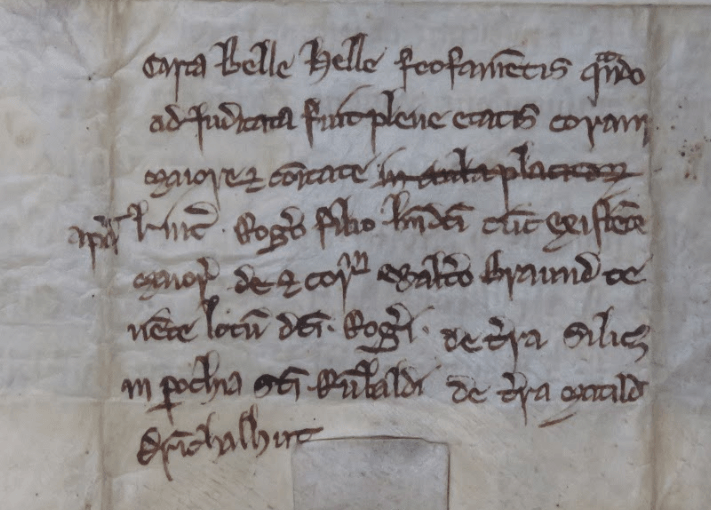

Bella’s father probably died whilst she was a minor, as the first grant she makes – to Henry the Illuminator of land once held by Matilda Drincalhut in the parish of St Rumowld – includes an endorsement that she has made the document, being judged to be now in her majority, before the mayor and commonalty of Lincoln, when Roger son of Benedict was mayor, This is probably the first time Roger was mayor (around 1267, although Hill says 1275).

In two other grants of c. 1269, when William Holgate was first mayor, she grants more land in the parish of St Rumwold and land in St Bavon’s parish to the same Henry (very probably at the same time as the witness lists are near identical).

Each of these grants is in return for a halfpenny in lieu of service, but these halfpennies were then quitclaimed by Bella in favour of Henry for an even more nominal payment of a clove a year to Bella and her heirs, sometimes 1269-1273/4 (in one of the years that Holgate was mayor). This was not, though, the final piece of negotiation between Henry and Bella. Bella had retained a right in the property through the nominal service owed to her, and in 1275/6 (dated by the appearance in the witness list of Roger son of Benedict in his second period as mayor) the land in St Rumwold’s once held by Ralph the Tailor was re-granted, with identical boundaries, to Henry for 1d a year.

Two more, undateable documents also survive. In one Bella grants Henry the property in St Bavon’s mentioned in her 1269 document, but for an annual payment of 5d in lieu of service. There is also a more unusual document in which Matilda undertakes not to sell or alienate the property she owns in St Rumwold’s parish and with which she has enfeoffed Henry without Henry’s agreement. If she breaks this agreement, Henry is released form the 8s. a year he owes Bella at that point from property in St Bavon’s parish. Bella still gains in the short term at least in return for this this charter Henry has paid her twelve shillings sterling.

These seven documents show us Bella carrying out some shrewd business deals, apparently increasing in confidence over the ten or so years the deeds cover. If we look at her surviving seal impressions these also suggest a growth in confidence and status. Four of these seven documents have seals or fragments of seals on them, all of them according to the documents Bella’s own seal. They are not all, though, from the same matrix: Bella had at least three different matrices in this decade, and these changes both demonstrate something about Bella’s use of seals, and perhaps her attitude to sealing, as well as allowing us to place at least one of those undated documents in its correct place in the sequence of events.

Bella’s first document, the one issued when she was adjudged to be of age, has a round seal, with a simple radial design. The seal is in green wax, now repaired, what remains of the legend is nicely spaced, and the seal image appears to have been well carved if not of the highest quality. Such a simple design might well be what a young woman who finds herself needing her first seal might choose, and perhaps what she might be offered as an ‘off the peg’ matrix by an engraver.

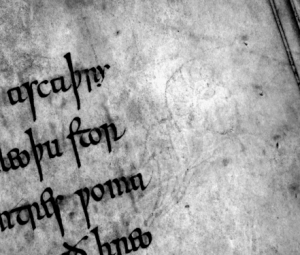

The next sealed document, from 1269-c.1273/4 uses a very different matrix, a pointed oval, now broken but with an image which appears to be an inverted stylised lily, or possibly a cross shaped radial design (the missing bottom half of the seal impression makes it hard to be certain) with the remaining legend reading ‘+ S’ BEL … LLE’. This seal too is of reasonable quality, with the double LL towards the end of the legend nicely spaced – similar in fact to that of her first seal and possibly by the same engraver. It may well be that Bella was already using this seal by c. 1269: the pattern of the remaining tag on her two documents dated from round that year suggests it once held a seal which was a pointed oval.

By c. 1275/6, when she re-granted property once held by Ralph the tailor to Henry for a higher rate of payment than previously, Bella was using a third matrix. This was another pointed oval, again with a stylised lily image upon it, but this time a more elaborate one, and with a different legend reading ‘+ SIGILLV…BEL…’. This matrix was of higher quality, with a better engraved image and a well-carved legend.

Probably this matrix was also used for the last of Bella’s documents which includes a seal. This again is a stylised lily, of the same form, and the legend again starts +SIGIL … The impression is not as sharp as that in the 1275 document, and it is just possible that this impression is from a fourth matrix, but equally likely that it represents a careless use of the matrix or a matrix which has become worn. This impression is found on Matilda’s guarantee not to alienate her messuage in St Rumwold’s parish without Henry’s agreement so this can probably be dated to near the end of this run of agreements.

So as Bella gains in confidence and status she changes her seal matrix, ending up with a higher quality and a slightly more individual image. Although these changes could be the result of lost matrices, the changes in style and quality suggest that Bella had made an active choice. Not all those who owned seal matrices changed them: even whilst changing their status and their description in their charters from daughter to wife to widow, women could retain the same seal. In such cases the owner’s feeling of identity with their matrix might lead them to keep it even as their life situation changed. In Bella’s case, however, it seems that changes in a matrix may be connected to changes in identity, revealing a different sort of relationship between sigillant, seal and matrix.

Philippa Hoskin

Westminster Abbey and the case of the lonely seal bag

Our last archive trip was to Westminster Abbey, where we spent four weeks squirrelled away in the muniments room: a mysterious space built on top of the cloisters, overlooking Poets’ Corner and within earshot of everything happening in the church below. We began to tell the time by the hourly prayers and knew it was time to pack up when the organ warmed up before evensong. We were incredibly fortunate to be able to spend such a long time riffling through boxes of documents and imaging their seals. There were so many seals that were interesting because of their owners, colours, shapes or designs but my favourite has to be the seal attached to Westminster Abbey Muniments 2022, dated to the first half of the fourteenth century.

There is something about using an image of the moment the written word is captured as a seal to validate the written word that really appeals to me.

More on the Westminster Abbey seals will follow. For now, I’d like to tell you about how we reunited a seal with its long-lost seal bag. As you might remember from our blog post on the Exeter Book , when we are in the archives we like to stick our noses in help out as much as we can by using our Crime-lite Imager creatively to try to solve problems or explore documents, books and artefacts to find out more about them. Towards the end of our final week in Westminster, the Keeper of Muniments showed us a seal bag that, according to a pencilled note written by somebody in the 1980s, had been found at the bottom of a box of documents. The bag was made of woven material and is a sort of goldy-green colour and it is clear from looking at it that there was some sort of pattern embroidered into it, but age had faded it so that the pattern was no longer discipherable. Having had good results retrieving lost writing, we wondered what results we would get by placing the seal bag under the Crime-lite Imager. Tweaking the wavelength down towards the red end of the spectrum, we were able to bring out the pattern on the material.

It’s an eagle! Challenge completed. Feeling rather cocky, we attempted one stage further: using fluorescence mode to see if any trace of the wax was left behind. If I’m honest, I was optimistically hoping for a complete outline of the impression of the seal: a sort of Turin shroud-esque trace left on the cloth of the seal bag. Realistically, that was never going to happen. However, we did manage to pick out a roughly circular area of the material that fluoresced at a different wavelength to the rest of the bag and did not coincide with the pattern. We had found the shape and size of the seal that the bag once contained. Taking careful measurements and comparing them to each seal that the Keeper of Muniments brought out of the box in which the bag was found, we found the only seal that would fit: the (now heavily restored) forged seal of Edward the Confessor.

We don’t know when the seal bag was made or if the material was originally intended to be used for a seal bag or had come from something else, such as vestments or an altar cloth. What we do now know is that at some point, somebody saw fit to use the eagle-patterned material to encase the “definitely real” seal of St. Edward. Perhaps it was the only nice piece of cloth of the right size or, perhaps, there was more thought behind it. One of the most famous legends associated with St. Edward tells us that he was riding on a pilgrimage to a chapel dedicated to St. John the Evangelist in Essex when a beggar asked him for alms. Edward had no money on him so gave him an expensive ring instead. A couple of years later two English pilgrims in the Holy Land were helped by a man wearing the ring who claimed to be John the Evangelist. He asked them to deliver the ring back to Edward and to tell him that he would meet him six months later in Heaven. We know that the eagle is often used in art to represent St. John. Could it be that whoever attached the seal bag wished to add weight to the authenticity by reminding the audience– those people living and working in Westminster Abbey who worshipped at the shrine of Edward the Confessor and knew his stories– of the special relationship between the two saints? That’s a mystery which may never be solved. We shall content ourselves with having solved the mystery of the lonely seal bag.

Hollie L. S. Morgan

Exciting Finds in the Exeter Book

If you follow us on Twitter, you will have noticed that when we are on our travels in different archives, we do our best to be as helpful (and, if we’re honest, as nosy) as we can. This means that as well as using our equipment to image seals and helping out by recording conservation issues or repackaging items as we go along, we occasionally try out our equipment on other things, to see if we can recapture anything thought lost, to separate out the colours in the thread used to mend a piece of parchment or just to see what happens. Our Crime-lite Imager, when teamed with our Forensic Light Source, can emit light from the entire spectrum, from Ultra violet to Infra-Red, so can be used to pick up writing which has faded away or to separate out details where there are intermingled materials that fluoresce at different wavelengths, such as plaited cord seal attachments.

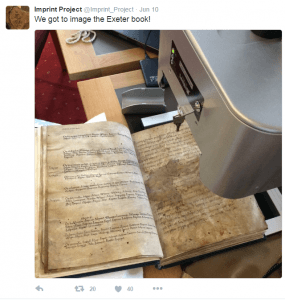

When we were in Exeter Cathedral archives, we were very excited to be allowed to use our equipment to have a quick look at the Exeter Book.

i. micel englisc boc be gewhilcum þingum on leoðwisan geworht

‘One large book in English concerning various subjects, composed in verse’

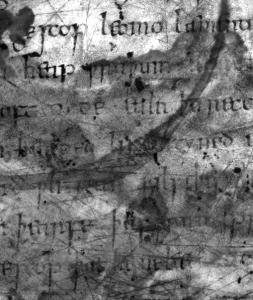

Granted UNESCO status in 2016 when it was added to the Memory of the World register, the Exeter Book is the largest and oldest surviving manuscript of English poetry. Within its 122 folios of statuesque Anglo-Saxon Square Minuscule script, saints’ lives, bestiary texts, maxims, elegies, homiletic texts, and nearly a century of Riddles are inscribed, made all the more incredible by the fact the manuscript was completed by a single scribe. However, despite being the “foundation volume of English literature”, (UNESCO, 2016) for much of its near 1000-year history, the codex has been abused more than used. Having survived for a period of time without a binding, the opening folios of the extant manuscript (ff.8r) have suffered from extensive staining and scoring; a ring-shaped mark (argued to be from a glue pot) sits square in its centre while the edges of the folio are defaced with repeated scoring from a knife, one of which has been crudely sewn back together. These stains affect not one but five folios of the manuscript through to f.13r/v. Forty folios further in, folio 53r/v has been cropped along its top edge, resulting in the loss of 8 lines of manuscript text of Canticles, while the final fourteen folios of the manuscript have suffered from the most significant damage of all: fire damage. This is the result, according to previous editors, of a ‘hot poker or a fire-brand’ being placed across the final folio, burning through the manuscript to f.115r and causing significant textual losses to the final set of Riddles, and a number of short poems (Judgement Day I to Ruin). That flecks of gold and silver can also be seen across a number of folios suggest that the manuscript spent some time being put to practical use in the scriptorium not only as a chopping board (as detailed above) but as a means of keeping gold and silver leaf flat; this repurposing of the codex may well have been key to its survival. Elsewhere, evidence of use rarely pertains to the contents: the manuscript includes a number of drypoint drawings (angels’ heads, vines, some litterae notabiliores, figures holding scrolls, and one – placed upside down on the folio – of a man riding a horse). Research undertaken in the 90s (Conner, 1993) suggests that some of these may have been present on the parchment prior to the manuscript being written, as the ink can be seen to ‘bleed into’ the drypoint lines in a number of places. We used our Crime-lite Imager to image some of these drypoint drawings.

The drypoint sketches were a joy to image. It helped, for a start, that we already knew they were there! Even more exciting for us, however, were the results of our imaging techniques on the text itself. Using various wavelengths of light, we digitally ‘pulled’ text from stains, separated it out from scratches and burn marks. We have given these images to Exeter Cathedral Library and Archives, so that the text can be preserved for future generations. They also raise interesting questions about whether all the stains were, in fact, produced after the manuscript was written.

We picked a folio almost at random and found some text that does not, at first glance, have any business being anywhere. Folio 33r has what appears to be one of the litterae notabiliores buried underneath the text, which we brought out for imaging using Infra-Red light from a forensic light source. We thought at first that the text was show-through from the other side, but the other side does not match up. Is part of the Exeter Book a palimpsest, or is something else going on? Either way, this discovery has implications for how we understand the book to have been put together. Is it re-used parchment or did it once have a different order than we now know it?

Like all good collaborative projects, we think sharing ideas and skills is vital to scholarship, so Imprint have teamed up with Dr. Johanna Green, a self-confessed Exeter Book obsessive at University of Glasgow. The manuscript has been the centre of her research for over a decade. Often described as a miscellany due to the unusual organisation of contiguous religious and secular texts, a number of more recent studies argue that the manuscript might be better understood as an anthology, within which smaller thematic units of poems can be identified; ‘the Exeter codex is a composite of miniature compositions of which the individual poems can be seen as parts.’ (Lochrie 1986: 323). Johanna’s own research has centred on the decoration and organization of the manuscript’s litterae notabiliores (Green, 2012) which – after extensive examination and analysis – reveals a hierarchical pattern of use that has so far gone relatively unnoticed, but which may indicate certain organisational principles, or visual cues to literacy.

It is clear from the large number of scholarly outputs to date that there is much still to be discovered about the Exeter Book and its contents. Our images taken while having a quick look at the manuscript reveal details not currently visible by the naked eye which may impact how we understand the production of the original manuscript and its use over time. We plan to secure some funding to go back soon and have a proper look at the Exeter Book using our equipment.

The Exeter Book has not given up all its secrets just yet.

Hollie L. S. Morgan and Johanna M. E. Green

The Small Matter of the Hereford Jury Seals

Hereford Cathedral Archives (HCA): No. 649

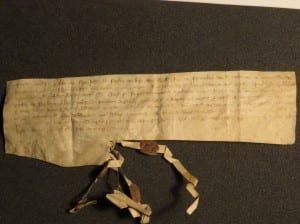

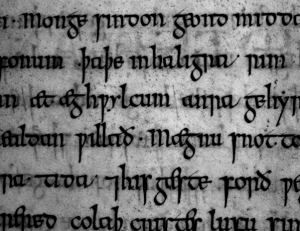

Of all the documents the team examined at Hereford Cathedral Archives, probably the most interesting personally were also the most unassuming. Hereford possesses a small set of jury verdicts dating from the early 14th century. These are pretty much as they sound, a written record of a jury’s verdict, in these instances relating to criminal trials. Most importantly for the project, the jurors each attached their seals as authentication of the verdict. While the amount of surviving judicial material in England is not insignificant by the late 13th and early 14th centuries, surviving verdicts with seals are comparatively very rare.

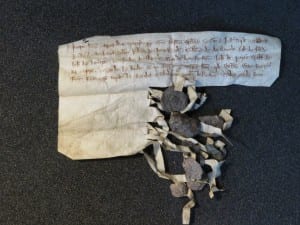

The verdicts are written on very small bits of parchment. Strips (known as tongues) were cut horizontally into the parchment at the bottom and the seals were attached on these, often with several seals to each tongue. The names of the jurors themselves are usually listed in the verdict, though we currently cannot match seals to names. Below are the contents of the verdict. Many of the seal impressions are now obliterated, but the ones which do survive are varied, and some are quite sophisticated in their design. What is particularly striking about these, however, is the tiny size of the seals (see the photo below for a comparison with a 5p coin).

HCA : No. 648

Tuesday next after the Feast of St. Hilary.

Verdict of a jury in the court of Madely, consisting of Phillip Dypre, Hugh de Karewardin, John de Kinleye, William de Godeweye, Walter de Cobliton’, Adam de Murmal, Roger de la Hyde, Walter son of Richard de Lolham, Richard de Abbrugge, Gilbert de Bellemere, Roger de Lolham, Robert de la Hull’, to the effect that Hugh son of William de la Bache is a thief and broke into the house of Hugh the smith of Madely and the house of Walter the smith of the same and stole flour and horseshoes and other goods, and the house of Margery de la Bache and stole woollen cloth and other goods.

Interestingly, the small size of Hereford’s surviving jury seals are also repeated in another type of criminal document dating from 1346. This is a receipt from four men to the sheriff of Hereford for assuming from the sheriff the responsibility of guarding a murder suspect until to his court appearance (see below, HCA 1116).

These are the smallest seals that the project has come across to date and, despite the fragmentary condition of some of them, they show a marked similarity in size. This in itself is intriguing. Is this related to the social status of the seal owners? Are they perhaps related by a common place or person of manufacture? Or are these seals perhaps peculiar to certain forms of documents, particularly those relating to criminal justice? If the latter, does it extend beyond Herefordshire? These are all questions which we will be exploring further.

Fergus PW Oakes