As you might remember, a few months ago we spent the day in a lab using medieval recipes to make sealing wax. We had been careful to ensure that we had followed the recipes as closely as possible in order to replicate the methods used in the Middle Ages (ignoring the fact that medieval seal makers tended not to frequent state-of-the-art conservation labs…), but we were curious to know the extent to which our sealing wax was authentically ‘medieval’. Our friends in Conservation said they could help us with that, and so we took our wax over to a different lab, where we used a Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectrometer to have a look at the chemical composition of our wax.

“What is a Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometer?”, I hear you ask. Well, it is a clever machine that uses a mathematical model called a Fourier Transform to measure the absorption or emission of infrared by the material (in our case, sealing wax). The bonds between elements absorb infrared of different frequencies, which then causes them to vibrate. The FTIR spectrometer shines monochromatic infrared light onto the wax, records how much of the light is absorbed, and then repeats at different wavelengths until a complete picture can be formed.

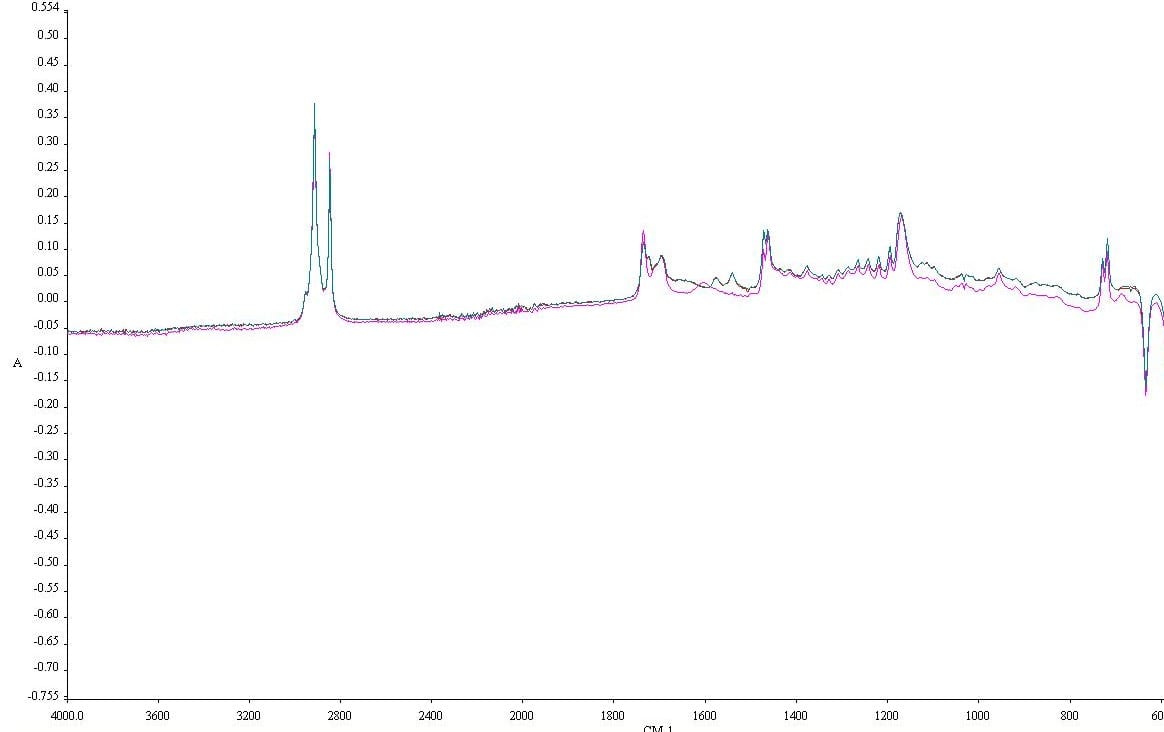

We can see from the readout that our red and green bits of wax had a similar composition, which is reassuring as beeswax and resin were used in both, but that verdigris and vermillion did make some difference to the ways in which the bonds were formed.

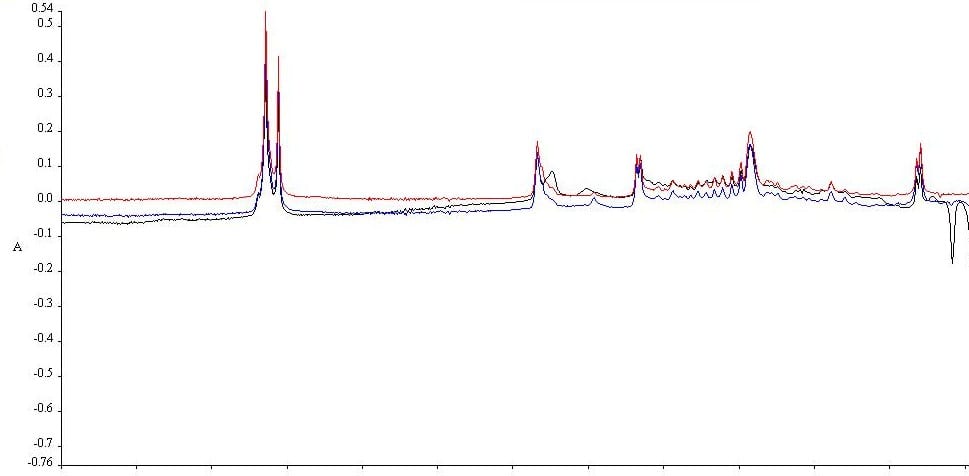

Our friends in Conservation then placed a piece of our red wax inside a magical Artificial Aging Chamber. An Artificial Aging Chamber uses heat and humidity to replicate the aging process, as warm, wet conditions speed up reactions. It is estimated that every 5-10°C doubles the rate of aging. Our wax was put in at 40% humidity and 40°C (any higher and it would have started to go soft) for about a month, and so was ‘aged’ by about 40 years. We then did some more FTIR spectroscopy. We compared the aged piece of wax to the unaged wax and also against a piece of wax from a seal of Richard II.

As you can see, the black (aged wax) and blue (Richard II seal) lines are much closer together than the blue and red (unaged wax) lines. There is some variation, as we do not know the recipe used to make Richard II’s seal. This is an ongoing project, and we intend to continue aging our wax and analysing its composition, but we can see that as our freshly-made ‘medieval’ wax ages, it becomes more like ‘medieval’ wax as we know it.

Hollie L. S. Morgan