Today is International Women’s Day, and Imprint thought this would be a good time to tell you the story of a shrewd medieval businesswoman, from her first steps as an adult in her teens to holding an established position in her community.

In 1965 Francis Hill, writing on Medieval Lincoln, used some of the Dean and Chapter deeds to describe what was happening in the thirteenth-century Lincoln suburb of Butwerk. He described land in St Rumbold’s parish there ‘which once belonged to Matilda Drincalhut whose name suggests a street cry and its appropriate trade. Here too were Henry the illuminator, and Ralf the tailor’ (p. 161). All of this is true, but Hill ignores the person who is central to all these grants. When Imprint came to look at the deeds and the attached seals we found that the documents Hill used were all granted by one woman – Bella daughter of Alan Helle (once called Bella daughter of Alan of Glentworth) and that the sealing as well as the documents told us much more about Bella.

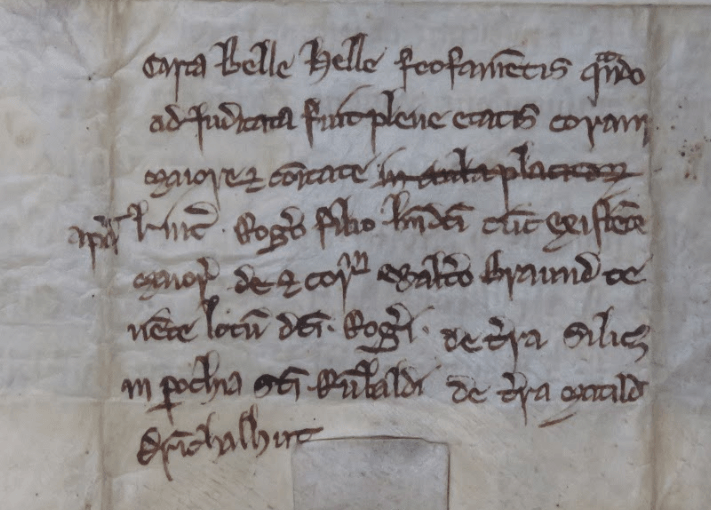

Bella’s father probably died whilst she was a minor, as the first grant she makes – to Henry the Illuminator of land once held by Matilda Drincalhut in the parish of St Rumowld – includes an endorsement that she has made the document, being judged to be now in her majority, before the mayor and commonalty of Lincoln, when Roger son of Benedict was mayor, This is probably the first time Roger was mayor (around 1267, although Hill says 1275).

In two other grants of c. 1269, when William Holgate was first mayor, she grants more land in the parish of St Rumwold and land in St Bavon’s parish to the same Henry (very probably at the same time as the witness lists are near identical).

Each of these grants is in return for a halfpenny in lieu of service, but these halfpennies were then quitclaimed by Bella in favour of Henry for an even more nominal payment of a clove a year to Bella and her heirs, sometimes 1269-1273/4 (in one of the years that Holgate was mayor). This was not, though, the final piece of negotiation between Henry and Bella. Bella had retained a right in the property through the nominal service owed to her, and in 1275/6 (dated by the appearance in the witness list of Roger son of Benedict in his second period as mayor) the land in St Rumwold’s once held by Ralph the Tailor was re-granted, with identical boundaries, to Henry for 1d a year.

Two more, undateable documents also survive. In one Bella grants Henry the property in St Bavon’s mentioned in her 1269 document, but for an annual payment of 5d in lieu of service. There is also a more unusual document in which Matilda undertakes not to sell or alienate the property she owns in St Rumwold’s parish and with which she has enfeoffed Henry without Henry’s agreement. If she breaks this agreement, Henry is released form the 8s. a year he owes Bella at that point from property in St Bavon’s parish. Bella still gains in the short term at least in return for this this charter Henry has paid her twelve shillings sterling.

These seven documents show us Bella carrying out some shrewd business deals, apparently increasing in confidence over the ten or so years the deeds cover. If we look at her surviving seal impressions these also suggest a growth in confidence and status. Four of these seven documents have seals or fragments of seals on them, all of them according to the documents Bella’s own seal. They are not all, though, from the same matrix: Bella had at least three different matrices in this decade, and these changes both demonstrate something about Bella’s use of seals, and perhaps her attitude to sealing, as well as allowing us to place at least one of those undated documents in its correct place in the sequence of events.

Bella’s first document, the one issued when she was adjudged to be of age, has a round seal, with a simple radial design. The seal is in green wax, now repaired, what remains of the legend is nicely spaced, and the seal image appears to have been well carved if not of the highest quality. Such a simple design might well be what a young woman who finds herself needing her first seal might choose, and perhaps what she might be offered as an ‘off the peg’ matrix by an engraver.

The next sealed document, from 1269-c.1273/4 uses a very different matrix, a pointed oval, now broken but with an image which appears to be an inverted stylised lily, or possibly a cross shaped radial design (the missing bottom half of the seal impression makes it hard to be certain) with the remaining legend reading ‘+ S’ BEL … LLE’. This seal too is of reasonable quality, with the double LL towards the end of the legend nicely spaced – similar in fact to that of her first seal and possibly by the same engraver. It may well be that Bella was already using this seal by c. 1269: the pattern of the remaining tag on her two documents dated from round that year suggests it once held a seal which was a pointed oval.

By c. 1275/6, when she re-granted property once held by Ralph the tailor to Henry for a higher rate of payment than previously, Bella was using a third matrix. This was another pointed oval, again with a stylised lily image upon it, but this time a more elaborate one, and with a different legend reading ‘+ SIGILLV…BEL…’. This matrix was of higher quality, with a better engraved image and a well-carved legend.

Probably this matrix was also used for the last of Bella’s documents which includes a seal. This again is a stylised lily, of the same form, and the legend again starts +SIGIL … The impression is not as sharp as that in the 1275 document, and it is just possible that this impression is from a fourth matrix, but equally likely that it represents a careless use of the matrix or a matrix which has become worn. This impression is found on Matilda’s guarantee not to alienate her messuage in St Rumwold’s parish without Henry’s agreement so this can probably be dated to near the end of this run of agreements.

So as Bella gains in confidence and status she changes her seal matrix, ending up with a higher quality and a slightly more individual image. Although these changes could be the result of lost matrices, the changes in style and quality suggest that Bella had made an active choice. Not all those who owned seal matrices changed them: even whilst changing their status and their description in their charters from daughter to wife to widow, women could retain the same seal. In such cases the owner’s feeling of identity with their matrix might lead them to keep it even as their life situation changed. In Bella’s case, however, it seems that changes in a matrix may be connected to changes in identity, revealing a different sort of relationship between sigillant, seal and matrix.

Philippa Hoskin