Our last archive trip was to Westminster Abbey, where we spent four weeks squirrelled away in the muniments room: a mysterious space built on top of the cloisters, overlooking Poets’ Corner and within earshot of everything happening in the church below. We began to tell the time by the hourly prayers and knew it was time to pack up when the organ warmed up before evensong. We were incredibly fortunate to be able to spend such a long time riffling through boxes of documents and imaging their seals. There were so many seals that were interesting because of their owners, colours, shapes or designs but my favourite has to be the seal attached to Westminster Abbey Muniments 2022, dated to the first half of the fourteenth century.

There is something about using an image of the moment the written word is captured as a seal to validate the written word that really appeals to me.

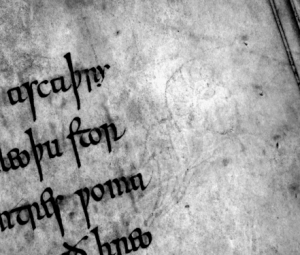

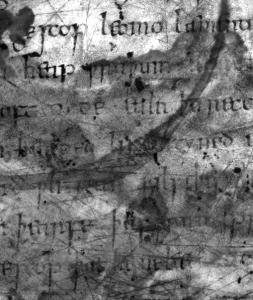

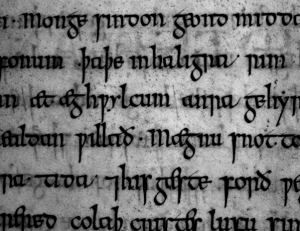

More on the Westminster Abbey seals will follow. For now, I’d like to tell you about how we reunited a seal with its long-lost seal bag. As you might remember from our blog post on the Exeter Book , when we are in the archives we like to stick our noses in help out as much as we can by using our Crime-lite Imager creatively to try to solve problems or explore documents, books and artefacts to find out more about them. Towards the end of our final week in Westminster, the Keeper of Muniments showed us a seal bag that, according to a pencilled note written by somebody in the 1980s, had been found at the bottom of a box of documents. The bag was made of woven material and is a sort of goldy-green colour and it is clear from looking at it that there was some sort of pattern embroidered into it, but age had faded it so that the pattern was no longer discipherable. Having had good results retrieving lost writing, we wondered what results we would get by placing the seal bag under the Crime-lite Imager. Tweaking the wavelength down towards the red end of the spectrum, we were able to bring out the pattern on the material.

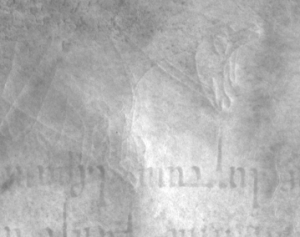

It’s an eagle! Challenge completed. Feeling rather cocky, we attempted one stage further: using fluorescence mode to see if any trace of the wax was left behind. If I’m honest, I was optimistically hoping for a complete outline of the impression of the seal: a sort of Turin shroud-esque trace left on the cloth of the seal bag. Realistically, that was never going to happen. However, we did manage to pick out a roughly circular area of the material that fluoresced at a different wavelength to the rest of the bag and did not coincide with the pattern. We had found the shape and size of the seal that the bag once contained. Taking careful measurements and comparing them to each seal that the Keeper of Muniments brought out of the box in which the bag was found, we found the only seal that would fit: the (now heavily restored) forged seal of Edward the Confessor.

We don’t know when the seal bag was made or if the material was originally intended to be used for a seal bag or had come from something else, such as vestments or an altar cloth. What we do now know is that at some point, somebody saw fit to use the eagle-patterned material to encase the “definitely real” seal of St. Edward. Perhaps it was the only nice piece of cloth of the right size or, perhaps, there was more thought behind it. One of the most famous legends associated with St. Edward tells us that he was riding on a pilgrimage to a chapel dedicated to St. John the Evangelist in Essex when a beggar asked him for alms. Edward had no money on him so gave him an expensive ring instead. A couple of years later two English pilgrims in the Holy Land were helped by a man wearing the ring who claimed to be John the Evangelist. He asked them to deliver the ring back to Edward and to tell him that he would meet him six months later in Heaven. We know that the eagle is often used in art to represent St. John. Could it be that whoever attached the seal bag wished to add weight to the authenticity by reminding the audience– those people living and working in Westminster Abbey who worshipped at the shrine of Edward the Confessor and knew his stories– of the special relationship between the two saints? That’s a mystery which may never be solved. We shall content ourselves with having solved the mystery of the lonely seal bag.

Hollie L. S. Morgan